1 Introduction

Clinical gene testing easily generates vast volumes of raw sequencing data. Without proper perspective of its utility and of a reporting frameworks, these measurements remain dumb and difficult to report in a compact and relevant way. Therefore, laboratories must consider how to convert the data into structured information that supports reproducible interpretation and transparent communication with patients, clinicians, and the clinical research community at large.

Reporting on NGS observations requires an organisation of technical, analytical, and interpretive details into a structured, possibly even standardised document that will inform diagnosis, prognosis, or therapeutic decision-making. Reporting also means knowing and stating limitations about what remains outside the capabilitie of the measurement technology. Reports that follow established either national or otherwise best practice guidelines and regulatory expectations reduce variability, ensure compliance, and safeguard patient outcomes.

Without pretending there is one framework that fits all needs, this article attempts to identify central elements of a good report of an NGS-based genetic test. It outlines elements pertaining to the DNA preparation, sequencing, bioinformatic pipeline, annotation and prioritisation components.

2 What genetic diagnostic tests?

In its simplest form a well targeted NGS-based genetic diagnostic test should answer a single straightforward medical question. The test is specific to a given condition and serves to confirm a diagnosis and trigger some actions. Is the decreased production of hemoglobin resulting in anemia or a chronic heart problem an inherited condition for the patient or is it the consequence of some other physiological problem? Will a particular drug be suitable for treating a patient or not is another typical test case where a genetic test might provide an answer.

Making the diagnosis of Alport syndrome is critical because effective inexpensive treatment with renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) blockade delays the development of kidney failure. A genetic test for mutations in a few specific genes can be highly informative (Gross et al. 2020, DOI: 10.1016/j.kint.2019.12.015). The test report then serves as the communication medium between the sequencing laboratory and the clinician or researcher who applies the results in a medical or scientific context.

Now the human genome has potentially multiple versions of about 20’000 genes, and therefore, in more complicated cases, comprehensive genetic testing over multiple, even thousands of genes, or even in regulatory regions outside of genes can be the only way to get a sufficient – albeit seldom complete – understanding of the underlying factors of a condition. We are here talking typically about either rare diseases where very little of the genetics is known, or about situations where a faulty interplay between multiple genes can lead to the medical condition of a patient, for example cancer.

And this is without considering that the genetic component can be insufficient on its own in explaining a medical condition, the environmental component playing its own part in the whole. Making the diagnosos of ASD (autism spectrum disorder) is important for gaining a better understanding of an individual’s strengths and challenges, and for accessing needed support and services. For children, early diagnosis allows for timely intervention, which can lead to improved developmental outcomes. For adults, it can provide self-acceptance and access to accommodations in education and employment, and help them connect with support communities. However, as ASD is a multifactorial neurodevelopmental condition there is no single test for autism, even less so a genetic test, and much effort is dedicated to the understanding of it (Salenius et al. 2024, DOI: 10.1186/s12888-024-06392-w ). In analogous cases, the genetic test report can at most be a part of an otherwise more comprehensive report.

Reporting on such different situations will obviously require some sections of the report to be adapted to the purpose of the test and case at hand.

3 Genetic screening tests are not diagnostic

There are of course other situations where the analysis of a part of the genome can be useful. Forensic testing in the sense of identifying someone is a prime example, but there are also other situations where a genetic test carries a considerable amount of value. While a diagnostic test identifies a specific genetic conditions in an individual, often performed when some symptoms are present, a genetic screening test identifies individuals in a population. Generally the aim of a screening is to identify among symptomless individuals those who may be at risk for a specific genetic condition. A specific type of screening is the testing of two persons (or donors) in view of identifying carriers of risk factors that could be inherited by a descendant.

Due to this fundamental difference in purpose between diagnostic and screening tests, reporting on the latter is quite different from reporting on genetic diagnostic tests, although the underlying methodology is identical.

4 What about NGS as a measurement technique?

Next generation sequencing as a measurement principle targeting DNA implies to repeatedly trying to read short pieces from a mixture of millions of molecules originating from the region of interest defined by the purpose of the test. Each piece of the region of interest of the genome is potentially slightly different, and so is the reading of each piece. Therefore, one can say that next generation sequencing is about gathering sufficient data about multiple fragments of DNA representing the region of interest. The process of so to say reading every piece in the mixture is not failproof, and the method therefore aims at providing a large amount of slightly different readings of slightly different molecules. The NGS method is thus based on a stochastic process integrating data provided from a collection of random variables, representing this double diversity in a probabilistic way. A key question therefore boils down to assessing not only the the genetic test raw data but also the probability of it being correct, something to document in the report.

5 The complexity of the genome

The genome region of interest for a test is, if possible, defined on the basis of functional information that is available about the genome. The genome is far from homogenous and regular both from a functional organisation and molecular DNA content such as the frequency of the different bases or the complexity of the sequence formed by them. The human genome is the result of an evolution spanning a very long time period and as a result of this evolution some parts of the genome have gained in functional importance while others have lost or even become redundant. There are thus some regions of the genome that are more difficult to sequence due to their DNA sequence repetitivity and one cannot be totally sure whether the sequencing process has captured data from the region of interest or from another region with high similarity but less relevant from a functional perspective. This basic biological complexity has its own bearing on the reporting as well.

6 The ever changing knowledge landscape

A genetic test generally reports variants in the gene sequence, in other words divergence, and the understanding of the functional implications of this divergence. Interpretation of the measured divergences is based on ever growing understanding that is available from fundamental research on the genome and the function of its different regions. As this understandings evolves and more information becomes available, so will the interpretation. The genetic test report is therefore strongly bound to the biomedical and functional knowledge about the genome that is available at the time of analysis. A renewed analysis can therefore at a later time point bring understanding not accessible at the moment of the original report.

7 After all, what is normal?

Divergence, in other words genetic variants have to be measured in comparison to something – or to many things. In gene testing one compares divergence to what is called a reference genome. Any divergence from the reference is a variant. The first version of an incomplete human genome was published at the beginning of the millenium. Since then the sequence of this reference genome has been updated multiple times, bringing in corrections to existing errors and new sequence to parts of the genome that had not previously been sequenced (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/grc/human).

The latest clinically relevant human genome version is GRCh38.p14 (November 2022). It does not any more represent any single human being but is in stead of compilation of the most ‘normal’ or frequent sequences based on a multitude of data sources and considerations. There will continue to be updates publicly available at regular intervals in the form of patch releases to the main version 38. However, it has been decided to indefinitely postpone next coordinate-changing update (GRCh39) while the genome consortium evaluates new models and sequence content from ongoing efforts to better represent the genetic diversity of the human pangenome, including those of the Telemore-to-Telomere Consortium and the Human Pangenome Reference Consortium.

Different populations show different type of ‘normality’, in other words any identified variant in a patient can well have different level of presence in different populations. This means that the relevance of a variant in a patient gene test is not only a function of the variant itself but also of the underlying population frequency of that variant. Normality in South-East Asian populations is different from that in a European one. Some populations even show small pockets of very ‘unusual’ normality (Charoenngam et al. 2025, DOI: 10.1186/s13023-025-04160-x ) in terms of variant frequencies and relevance.

ClinGen provides regularly updated guidance regarding the use of variant population frequencies provided by gnomAD version 4 (https://clinicalgenome.org/site/assets/files/9445/june_2025_communication_to_clingen_vceps_from_clingen_vcep_review_committee.pdf). These guidelines are frequently assessed in various specific contexts, showing that their use is not black and white but requires contextualised additional knowledge to discern what is normal and what not (Wang et al. 2024, DOI: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2024.104909).

8 From DNA via raw NGS data to genetic variants

Not only the quality of the wet lab work, DNA purification, library construction are critical; also the sequencing itself and the ensuing data analysis are. Computational tools are used to identify the divergence from the reference genome by using the measurement raw data. It takes a few critical bioinformatic software procedures to convert the raw sequence data to a list of identified variants. Some of the computational steps are heuristic, meaning that the alignment and variant calling is proceeding by trial and error or by rules that are only loosely defined. By applying strict and comprehensive quality control it is possible to ensure that the identified genetic variants can be trusted and that the absence of variants does not just depend on a badly covered region during sequencing. A good report will include relevant metrics to document the correctness of the procedure of the genetic test.

The observations shall also be recorded using formats and nomenclature that can be understood and this means in practice to apply certain standards that have been developed by professionals. The HGVS Nomenclature is an internationally-recognised standard for the description of DNA, RNA, and protein sequence variants. It is used to convey the definition of variants in clinical reports and to share variants in publications and databases. There is an HGVSg standard for genomic location, HGVSc for transcript location, and HGVSp for amino acid location. The latter two are dependent on the selected transcript and can therefore not be used without also specifying the transcript for which the numbering applies. There is a general understanding of using the canonical or the MANE transcript, but this has sometimes to be adjusted as non-canonical transcripts are more abundantly used in some tissues than in others. The HGVS Nomenclature is administered by the HGVS Variant Nomenclature Committee (HVNC) under the auspices of the Human Genome Organization (HUGO) (den Dunnen et al. 2016, DOI: 10.1002/humu.22981; Hart et al. 2024, DOI: 10.1186/s13073-024-01421-5).

The VCF, or Variant Call Format, is used to ensure precise inter-system exchange of variant call data for research and clinical applications, together with any additional quality-related informatio. It is a standardised text file format used for representing SNP, indel, and structural variation calls. The VCF specification and other bioinformatic file specifications are now managed by the Genomic Data Toolkit team of the Global Alliance for Genomics and Health (Wagner et al. 2021, DOI: 10.1016/j.xgen.2021.100027).

Reporting should abide to these established formats to maximise the usability of a report.

9 Is every genetic variant equally relevant?

Obviously, every observed variant in a gene test does not carry the same importance from a functional perspective or in the given context of the condition of the tested person. Concerning relevance it is useful to discern two concepts present in normal language usage that have taken more specific significance when used for genetic variants. Firstly, variant classification is about assigning pathogenicity of variants based on established physical and functional criteria. Secondly, prioritisation is about ranking variants in terms of clinically significant in a given patient context, combining information about the patient with factors like gene, phenotype and condition, as well as inheritance patterns and variant occurrence in the population. The relevance of a variant is thus defined both in terms of classification and of prioritisation.

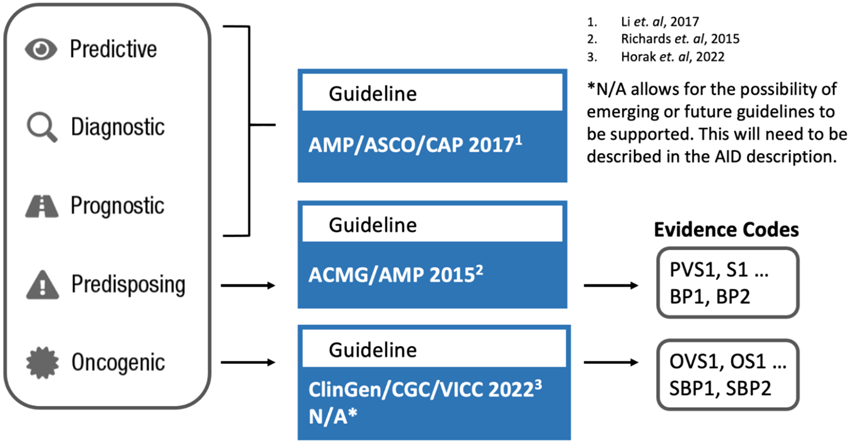

Figure 1: Assertion guidelines and their interdependence with particular focus on somatic variants but not only

10 Guidelines for asserting variant relevance

Variant analysis and reporting can follow different combinations of guidelines depending among other on whether the genetic test is about germline (constitutional) variants or about somatic ones (Fig.1). Predisposing assertion utilises generally the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology (ACMG/AMP) guidelines (Richards et al. 2015, DOI: 10.1038/gim.2015.30; Brandt et al. 2020, DOI: 10.1038/s41436-019-0655-2). In this system, variants are classified in five tiers from pathogenic to benign. For somatic predisposing variants there are the ClinGen/CGC/VICC guidelines (Mehta et al. 2021, DOI: 10.1007/s40291-021-00540-8; Horak et al. 2022, DOI: 10.1016/j.gim.2022.01.001). In this system, variants are classified in five tiers from oncogenic to benign via variants of unknow significance. National guidelines exist, such as those from the UK Association for Clinical Genomic Science (ACGS, https://www.acgs.uk.com/quality/best-practice-guidelines/).

Some – partially overlapping – guidelines are instructed by the condition of the patient as well, such as the ASCO/AMP/CAP guidelines. These provide a tiered system for classifying somatic variants in cancer based on their clinical significance for a given cancer type, using a four-tiered approach: Tier I (strong clinical significance), Tier II (potential clinical significance), Tier III (unknown clinical significance), and Tier IV (benign or likely benign). These guidelines, developed by the Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP), the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), and the College of American Pathologists (CAP), aim to standardise the interpretation and reporting of molecular results for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment.

11 Now to the report generation itself

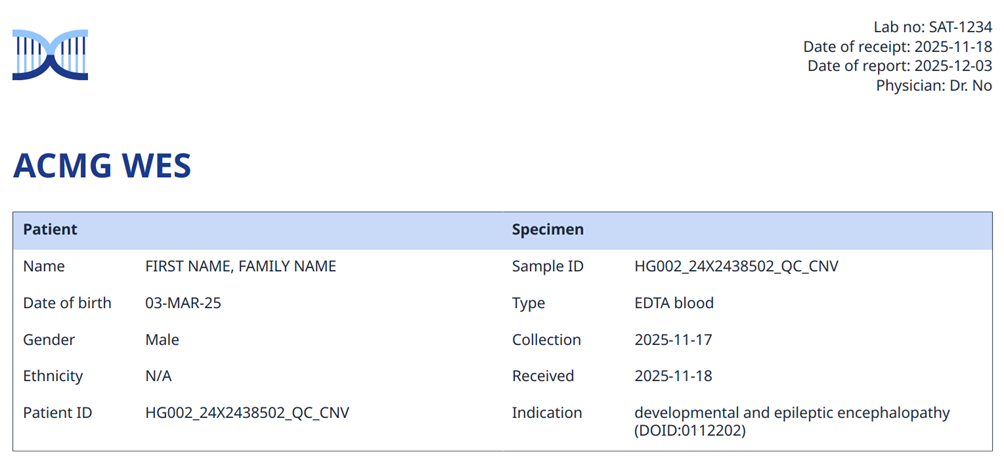

Report generation for a genetic diagnostic test compiles the interpreted results into a formal document. There will be the primary results, but possibly also secondary findings, carrier information, or variant risk alleles. The target reader can be either the patient itself, and/or the medical professional, in which case there will be differently adapted content. The date of the document will be indicating when it was created or became effective, and possibly implicitly or explicitly talk about update (see databases below). The document will contain information about the patient, the orderer of the test, the source of the biological material used, the test itself and the reason for applying it to the patient (Fig.2, example from the omnomicsNGS reporting system).

Figure 2: Example of report section on patient, orderer, and epicrisis

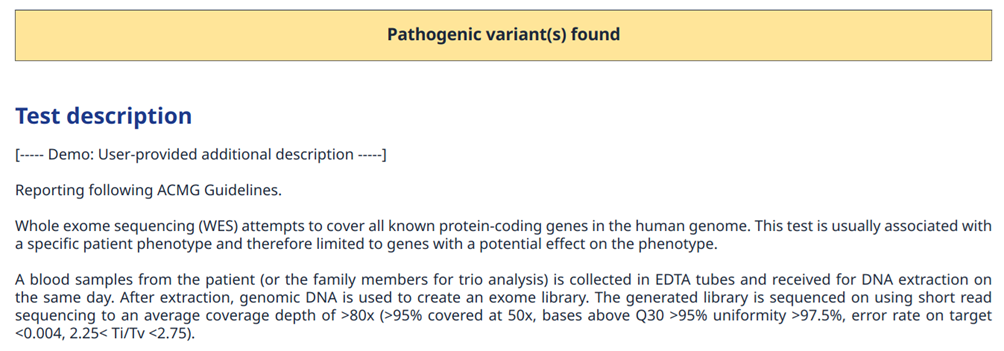

The report will then contain test result data organised into different sections. Firstly, the molecular sample preprocessing methodology, the sequencing itself, and the bioinformatic post-processing as well as variant interpretation shall be described enough to convey a general understanding of its overall power as well as limitations.

Figure 3: Example of report section with a brief test description

Secondly, the factual observation will be reported using standard descriptors, that, if needed, can be shared also outside of the laboratory structure performing the test.

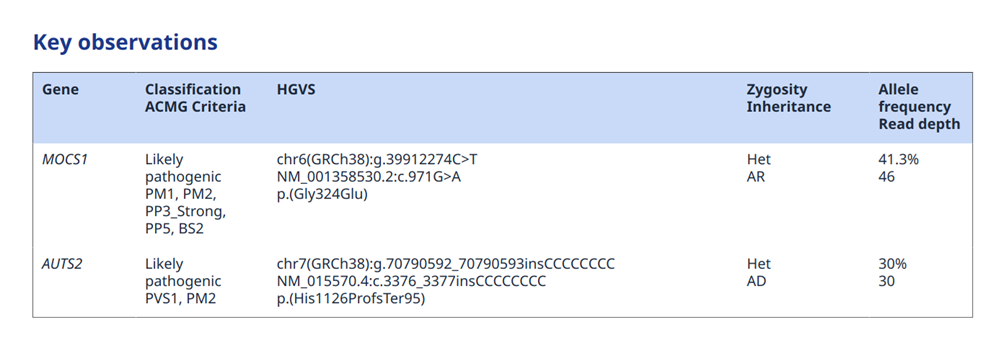

Figure 4: Example of report section with primary observations

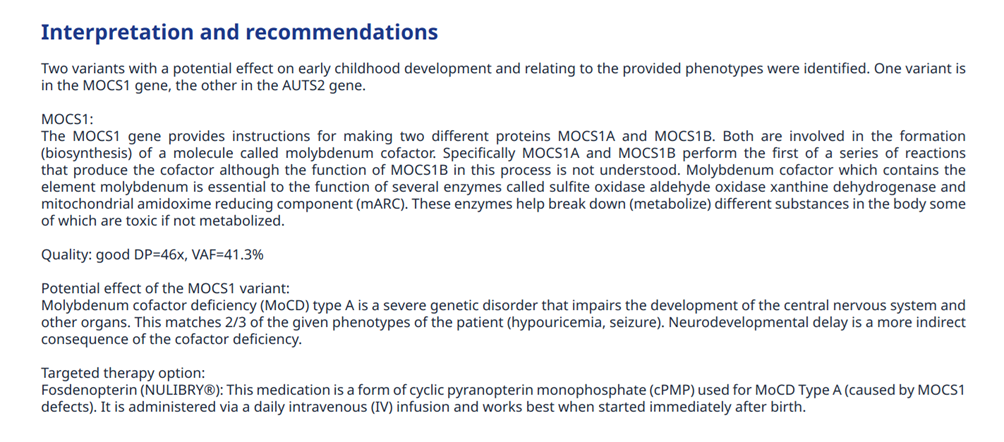

Thirdly, an analysis of the observations using the biomedical knowledge available at the moment of analysis is provided so as to support and guide the treatment of the patient. This can, or not, depending on the situation, be followed by treatment recommendations. However, this might be the task of another person than the analyst (Fig.5).

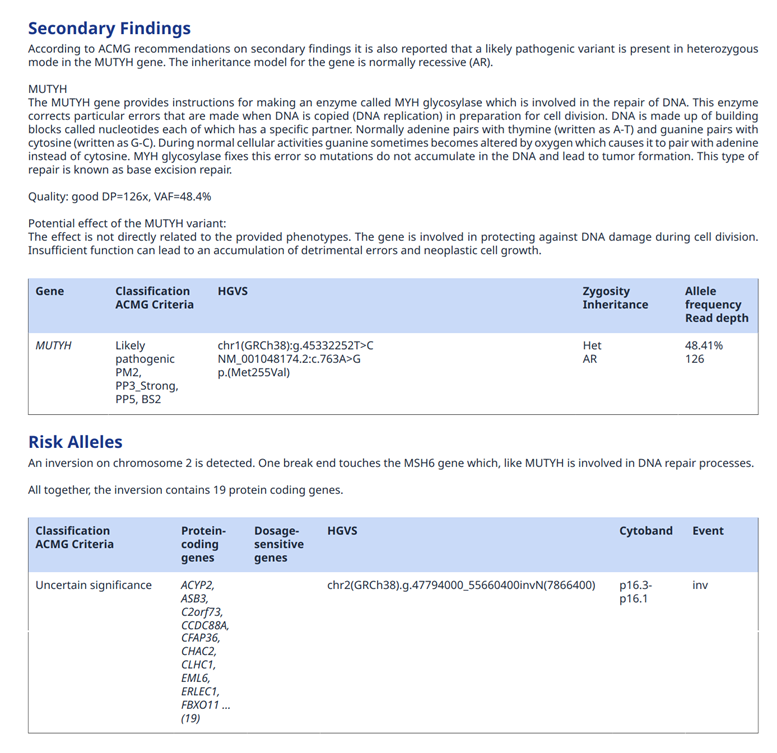

If different sections such as primary and secondary findings are presented, each of them will have their own analysis (Fig.6).

Figure 5: Example of report section with part of the key observations’ interpretation

Figure 6: Example of report section with secondary findings and more

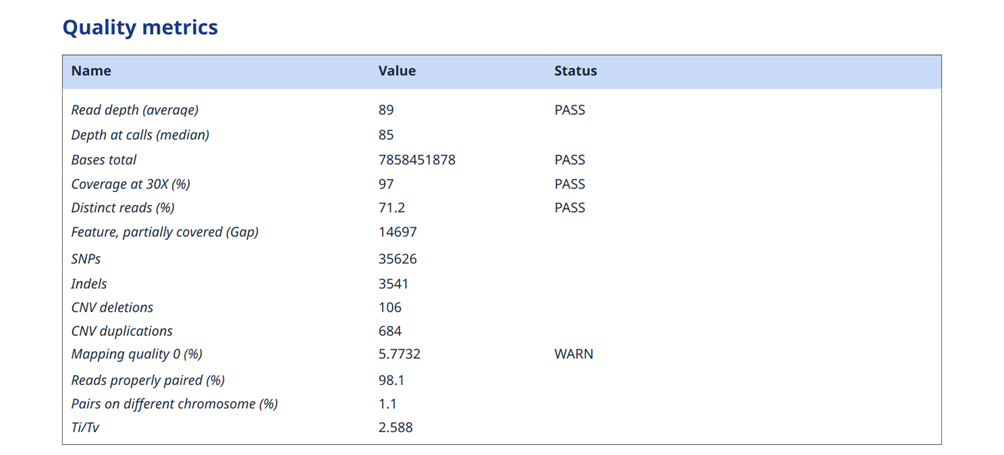

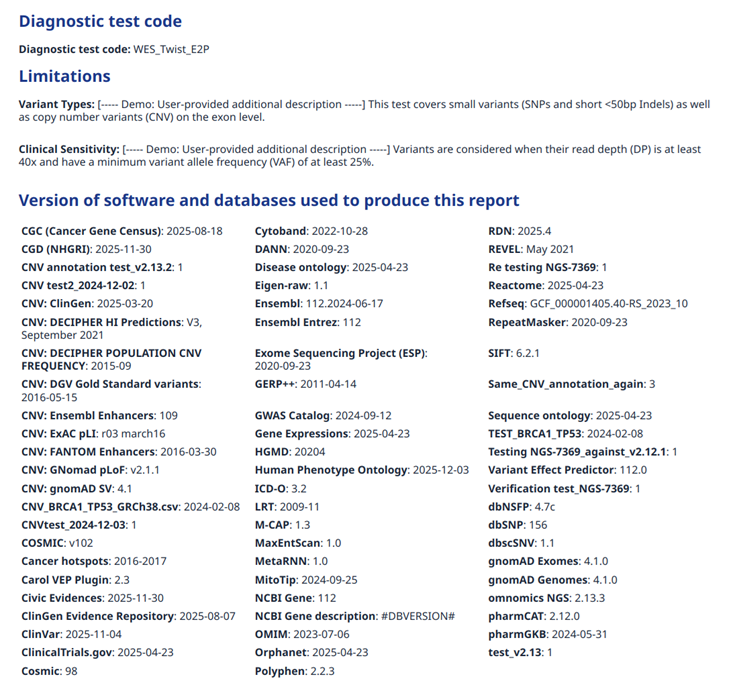

At the end, reference to the used analytical methodologies, statistics on the population level, databases used and their versions, as well as other more advanced data mining or artificial intelligence methods applied has to be provided. Also a section on the sample quality control statistics can be included either in the report itself, or in case more details are used it is recommended to provide it as a seprate QC report.

Figure 7: Example of report section on quality control of WES data

Figure 8: Example of report section on applied data sources for the annotations

These general guidelines will have to be adapted to the different types of genetic variants that are reported. Indeed, for small variants, quite precise knowledge is generally available. Structural variants, these being more difficult to compare to previously seen, will require a different approach to the annotation itself, and also the limit of present knowlege might be reached.